“How We Turned a Barren Construction Site Into A Gold Level Habitat In Less Than One Year"

Tracey Banowetz

Background

Our interest in using native plants in our landscaping began over twenty five years ago as two of our hobbies - gardening and birdwatching - intertwined. For Dave, reading Noah’s Garden by Sara Stein back in 1994 was like what reading Doug Tallamy’s Bringing Nature Home or Nature’s Best Hope is for many today. It showed how we could enjoy both hobbies in a way that also supported our more fundamental interests in nature and conservation.

Our first attempt at gardening with native plants was in conjunction with the construction of a new home in a Baton Rouge subdivision in 1995. We outgrew that space within five years and acquired 26 acres in the Tunica Hills north of St. Francisville. We enjoyed almost 20 years of fun in the woods before facing the fact that it was time to downsize. Which brings us to the start of the present-day story….

Initially, the concept of downsizing was depressing as we struggled with the thought of trying to shrink what we had in terms of both home and garden. What to keep? What to get rid of? And how? We needed a vision! We found it at an exhibit at the West Baton Rouge museum on the interior design concepts of Frank Lloyd Wright. Dave and I walked out of the exhibit, looked at each other, and said “That’s it! We keep nothing and go in a completely different direction.”

This meant swapping a 160 year old historic home and most of its contents for a small but intensely functional space based on the principles of Wright’s Usonian designs. But the characteristics of organic architecture - “creating harmony between human habitation and the natural world” - also provided an exciting step forward in our continuing interest in gardening with native plants.

So now we had to find a homesite. We looked for property on the New Orleans north shore in order to be closer to both of our mothers who still live in the area. We chose a 3/4 acre lot in the Money Hill subdivision in Abita Springs. We were attracted to Money Hill because of the conservation ethics expressed by the Goodyear family as well as their association with The Nature Conservancy. We chose our lot based on its gradual elevation change and the fact that it backed up to a small lake and a large common area with lots of space and lovely views. We knew our architect could help us do something really cool with the site.

Design Goals for the Home and Garden

In keeping with the principles of organic architecture, we wanted the construction of the home to be “dirt neutral.” In other words, we wanted as little fill and as little excavation as possible, despite the fact that the lot had a strong declining slope from front to back. The result was a split-level open u-shape home that melded into the existing topography. Pale green brick would further help the house blend in to its surroundings.

The changing elevation across the property created both challenges and opportunities. Managing the drainage in a sensitive way would be a challenge and for this we collaborated with Philip Moser Associates and installed a series of french drains and dry stream beds. A low retaining wall at the rear of the main garden in the front yard was added to retain both soil and soil moisture in this bed. Terraced steps in the rear compliment the geometry of the house, creating garden and lawn spaces that absorb water runoff from the roof. This also allowed us to preserve and protect a large longleaf pine in the backyard by avoiding any significant fill in its root zone.

Different elevations and exposures on the site offered us the opportunity to create three main habitat areas. The higher and sunnier front yard became the upland pine savannah; the lower, wetter northeastern corner became the lowland pine savannah or “flatwoods garden;” and the shadier west side became the woodland garden.

We were required to present a landscape plan to the Money Hill HOA prior to constructing our home. At the time we did this, the committee was primarily concerned with tree preservation and had some detailed requirements regarding the minimum number of trees you were required to have for each zone of your property. This was not a difficult target for us to meet and our initial plan was readily accepted. While the plan included a large planting area in the front yard for the upland pine savannah, there was also a generous amount of turf, which probably helped facilitate the approval. That said, current guidelines call for a minimum of 20% turf area in the front yard, so we have the opportunity to expand this garden as we learn more about what plants are most successful in this area. Thus far, the only “push back” we have received from the HOA was that it took longer than the required three months from move-in to install the garden.

Plant Selection

When it came to selecting specific plants for the gardens, we wanted to focus primarily on the use of indigenous native plant material common to the longleaf pine ecosystem that was original to the Money Hill area. Lucky for us, our best friends are Rick and Susan Webb who own the fabulous Louisiana Growers Nursery in nearby Amite. Having held my landscape horticulture license since 2002, we had easy access to some wonderful plant material, including lots of special selections that Rick has made from St. Tammany, Washington, and Tangipahoa parishes.

We also put into practice some of the principles we had recently learned from Claudia West and Piet Oudolf. We sought to use native grasses and perennials in relatively dense masses. Perennials were selected with an eye towards attracting birds, butterflies, and other pollinators. Many of our perennials came from Louisiana Growers, but we also discovered the great selection of perennials available as “landscape plugs” from Northcreek Nursery in Pennsylvania. Again, having my professional license allowed us access to this source of plant material. Using large quantities of smaller plants allowed us to achieve masses of plants quickly and economically.

Specific Plant Materials

While we focused on masses of perennials, we also opted for diversity in terms of both the woody and perennial selections. Having the three different habitats guided our selection process and accentuated this diversity. What follows is a list of some of the plant material in each of the three habitat gardens.

Upland Pine Savannah: This garden is in the front yard, receiving full sun with a southern exposure. The property slopes gently from the street down towards the house.

Butterfly Weed (Asclepias tuberosa), Yellow False Indigo (Baptisia sphaerocarpa), Rattlesnake Master (Eryngium yuccifolium), Coral Bean (Erythrina herbacea), Joe Pye Weed (Eupatorium fistulosum), Blue Arrow Rush (Juncus inflexus), Prairie Blazing Star (Liatris pycnostachya), Dense Blazing Star (Liatris spicata),Scarlet Beebalm (Monarda didyma), Peter’s Purple Bee Balm (Monarda fisulosa x barlettii), Spotted Beebalm (Monarda punctata), Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), Shortleaf Pine (Pinus echinata), Longleaf Pine (Pinus palustris), Prairie Coneflower (Ratibida pinnata), Orange Coneflower (Rudbeckia hirta), Giant Coneflower (Rudbeckia maxima), Pineywoods Dropseed (Sporobolus junceus), Stokes Aster (Stokesia laevis), Tree Huckleberry (Vaccinium arboreum).

Lowland Pine Savannah: This garden is in the rear northeastern corner of the property. It has significant elevation change across its area, staying drier at the top and much more damp at the rear.

Swamp Milkweed (Asclepias incarnata), Whorled Milkweed (Asclepias verticillata), American Hornbeam (Carpinus caroliniana), Button Bush (Cephalanthus occidentalis), Joe Pye Weed (Eupatorium fistulosum), Spiderlily (Hymenocallis liriosme), Dahoon Holly (Ilex cassine, “Tchefuncta”), Virginia Sweetspire (Itea virginica), Virginia Saltmarsh Mallow (Kosteletzkya virginica), Fetterbush (Lyonia lucida), Southern Wax Myrtle (Myrica cerifera), Longleaf Pine (Pinus palustris), Swamp Azalea (Rhododendron serrulatum), Florida Azalea (Rhododendron austrinum), Giant Coneflower (Rudbeckia maxima), Little Bluestem Grass (Schizachyrium scoparium), Wrinkleleaf Goldenrod (Solidago rugosa), Elliott’s Blueberry (Vaccinium elliotti).

Woodland: The woodland habitat stretches along the western side of the home, extending into the back yard area. It is bordered by the wooded lot next door which we bought half-way into the construction process in order to preserve the trees.

Common Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca), Butterfly Weed (Asclepias tuberosa), Crinum Lily (Crinum americanum), Dixie Wood Fern (Dryopteris australis), Southern Wood Fern (Dryopteris ludoviciana), Bigtop Lovegrass (Eragrostis hirsuta), Beeblossom (Gaura lindheimeri), Yaupon (Ilex vomitoria), Mountain Laurel (Kalmia latifolia), Sweetbay Magnolia (M. virginiana var. australis), Sourwood (Oxydendrum arboreum), Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), Obediant Plant 'Miss Manners’ (Physostegia virginiana), Longleaf Pine (Pinus palustris), Live Oak (Quercus virginiana), Florida Azalea (Rhododendron austrinum), Piedmont Azalea (Rhododendron canescens), Orange Coneflower (Rudbeckia fulgida var fulgida), Dwarf Palmetto (Sabal minor), Scarlet Sage (Salvia coccinea), Autumn Sage (Salvia greggii), Salvia ‘Black & Blue’ (Salvia guaranitica), Blue eyed Grass (Sisyrinchium angustifolium), Indian Pink (Spigelia marilandica) Stokes Aster (Stokesia laevis).

Elsewhere on the property: There are several other smaller beds on the site, including foundation beds across the front of the home, and additional trees dotted about.

Beeblossom (Gaura lindheimeri), Virginia Sweetspire (Itea virginica), White Muhly Grass (Muhlenbergia cappillaris), Black Gum (Nyssa sylvatica var. sylvatica), Beardtongue (Penstemon digitalis) Correll's False Dragonhead (Physostegia correllii), Longleaf Pine (Pinus palustris), Mexican Plum (Prunus mexicana), Water Oak (Quercus nigra), Nuttall Oak (Quercus nuttallii), Needle Palm (Rhapidophyllum hystrix), White Flame Salvia (Salvia farinacea x longispicata), Blue eyed Grass (Sisyrinchium angusstifolium), Wrinkleleaf Goldenrod (Solidago rugosa), Pond Cypress (Taxodium distichum var. nutans).

Bog Planter: I have long had a passion for collecting carnivorous plants and we designed a planter at the front entrance of the home to hold these.

Thread-leaf Sundew (Drosera filiformis var. tracyi), Spoon-leaf Sundew (Drosera spatulata), Starrush Whitetop (Rhynchospora colorata),

Pale Pitcher Plant (Saracenia alata), Yellow Pitcher Plant (Saracenia flava), White Pitcher Plant (Saracenia leucophylla), Parrot Pitcher Plant(Saracenia psittacina), Purple Pitcher Plant (Saracenia purpurea),

Catesby’s Pitcher Plant (Saracenia x. catesbaei).

Other Perennials: There are some non-native perennials that we just can’t live without and find particularly attractive to hummingbirds and butterflies. These have been included in other planters and beds around the home: Cigar Flower (Cuphea ignea), Shrimp Plant (Justicia brandegeeana), Lantana sp. ‘New Gold.’

Lot Next Door: As mentioned earlier, about half-way through construction, we had the opportunity to purchase the lot to the west of ours. We have begun to introduce more native trees, shrubs, and perennials into the understory. The list below includes both pre-existing and recently planted species.

Red Buckeye (Aesculus pavia), Green Milkweed (Asclepias viridis)

American Beautyberry (Callicarpa americana), Joe Pye Weed (Eupatorium fistulosum), Yaupon (Ilex vomitoria), Sweetbay Magnolia (M. virginiana var. australis), Southern Wax Myrtle (Myrica cerifera), Black Gum (Nyssa sylvatica var. sylvatica), Longleaf Pine (Pinus palustris), Loblolly pine Pinus taeda), Black Cherry (Prunus serotina), Common Hoptree (Ptelea trifoliata), Live Oak (Quercus virginiana), Winged Sumac (Rhus copallinum), Giant Coneflower (Rudbeckia maxima), Lyre Leaf Sage (Salvia lyrta), Tree Huckleberry (Vaccinium arboreum).

Outcome and Reception

As of this writing, it has been a little over twelve months since we installed most of the woody plant material. Perennials have just gone through their first winter and, for the most part, appear to have survived the recent cold snap. We are curious to see what Spring will bring. Our biggest challenge has been having to deal with the poor quality garden soil that was brought in to build some of the landscape beds. We’ve had to apply a lot more fertilizer than we’d like in order to lower the soil pH and improve fertility.

Overall though, the first year has been very rewarding. The abundance of milkweed brought lots of monarchs and countless caterpillars and chrysalis. Numerous other swallowtails, skippers, dragonflies, bees, and other pollinators have been spotted as well. Turtles come up from the nearby lake to lay their eggs in the garden which is fine with us. Various species of woodpeckers, flycatchers, warblers, and other songbirds have been spotted. We’ve had at least three different hummingbird species overwinter in the garden too.

The pandemic has prevented us from socializing much, so I can’t report on how the garden has been received beyond our immediate neighbors. Our next-door neighbor is an equally avid gardener with a completely different style, but she loves it and is always curious about what we are doing. Her granddaughter has even brought a chrysalis and a pitcher plant from our garden to show-and-tell! The young family across the street has expressed positive curiosity as well and recently inquired about our Certified Habitat sign.

I have to admit that I laughed when, in the middle of the admittedly drawn out process of initial installation, a member of the HOA committee asked when we would be finished. “Never!” We recognize that our garden will never be finished. It will always be evolving. As we learn from our successes and failures, we will probably reduce the turf and expand the garden in the front yard. We plan to “gently manage” the side lot by continuing to add appropriate trees, shrubs, and perennials to the understory. We look forward to enjoying our garden and its critters for many years to come!

Tracey Banowetz is past president of the Louisiana Native Plant Society and owner of WildWing Gardens, specializing in gardens for birds, butterflies, and wildlife. She lives and gardens with her husband David in Abita Springs, Louisiana.

Preliminary landscape design showing 3 habitat areas

Front elevation before landscaping

Front elevation after landscaping

Rear elevation before landscaping

Rear elevation after landscaping

Read the

Read the

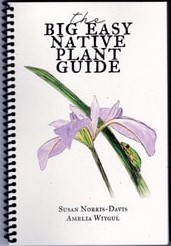

THE BIG EASY NATIVE PLANT GUIDE written specifically for the greater New Orleans area by our own Susan Norris-Davis is now available after many months of development! It includes 47 species for both sun and shade, vetted for ease of growing, suitable for small city gardens, and available locally at listed sites. It is beautifully illustrated (Amelia Wiygul) and thoroughly researched. Printed locally in the Lower 9 at Paper Machine on 100% post-consumer fiber recycled paper. It will be for sale at the

THE BIG EASY NATIVE PLANT GUIDE written specifically for the greater New Orleans area by our own Susan Norris-Davis is now available after many months of development! It includes 47 species for both sun and shade, vetted for ease of growing, suitable for small city gardens, and available locally at listed sites. It is beautifully illustrated (Amelia Wiygul) and thoroughly researched. Printed locally in the Lower 9 at Paper Machine on 100% post-consumer fiber recycled paper. It will be for sale at the

Coreopsis tinctoria, also known as Plains Coreopsis, is an annual species, lasting only one season, and can be seen growing wild on disturbed roadside areas, but is also a gardener’s favorite. These fast-growing plants can be direct seeded into garden beds and pots or planted out as plants. They always reward with a multitude of bi-colored flowers with yellow petals, red-brown at the base and brown center discs. The flowers are carried above airy, finely cut foliage on tall plants at 2-4 feet. They respond very well to pinching or cutting back when young to produce a denser, more branched plant. There are variations of C. tinctoria that present very pale yellow, ivory or mahogany red petals. Again, C. tinctoria prefers well drained and full-sun situations and can handle poorer soils. It is easy to collect seed or just allow this plant to re-seed itself in the garden.

Coreopsis tinctoria, also known as Plains Coreopsis, is an annual species, lasting only one season, and can be seen growing wild on disturbed roadside areas, but is also a gardener’s favorite. These fast-growing plants can be direct seeded into garden beds and pots or planted out as plants. They always reward with a multitude of bi-colored flowers with yellow petals, red-brown at the base and brown center discs. The flowers are carried above airy, finely cut foliage on tall plants at 2-4 feet. They respond very well to pinching or cutting back when young to produce a denser, more branched plant. There are variations of C. tinctoria that present very pale yellow, ivory or mahogany red petals. Again, C. tinctoria prefers well drained and full-sun situations and can handle poorer soils. It is easy to collect seed or just allow this plant to re-seed itself in the garden.